The Life of Bhagat Singh Thind: A Pioneer in the Fight for Equality and Spiritual Enlightenment

Introduction

Bhagat Singh Thind, born in the late 19th century in colonial India, emerged as a multifaceted figure whose life encapsulated the struggles of immigration, racial discrimination, military service, and spiritual advocacy in early 20th-century America. As an Indian-American Sikh, Thind's journey from a small village in Punjab to the halls of the U.S. Supreme Court symbolized the broader fight for citizenship rights among South Asians in the United States. His landmark case, United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), highlighted the arbitrary racial classifications that defined American naturalization laws, influencing immigration policy for decades. Beyond his legal battles, Thind was a prolific writer, lecturer, and spiritual teacher who blended Sikh philosophy with Western transcendentalism, inspiring audiences across the country. His service in the U.S. Army during World War I as one of the first turbaned soldiers further underscored his commitment to his adopted homeland, even as it repeatedly rejected him. Thind's life, spanning from 1892 to 1967, reflects themes of resilience, identity, and the pursuit of universal truth, making him a pivotal figure in Asian American history.

Early Life in India

Bhagat Singh Thind was born on October 3, 1892, in the village of Taragarh Talawa, located in the Amritsar district of Punjab, India. At the time, Punjab was under British colonial rule, a period marked by growing unrest and calls for independence. Thind grew up in a Sikh family, immersed in the teachings of Sikhism, which emphasized equality, service, and spiritual devotion. His father worked as a junior police officer, providing a modest but stable upbringing for Thind and his two younger brothers. From a young age, Thind displayed intellectual curiosity and a strong sense of justice, qualities that would define his later activism.

Education played a crucial role in shaping Thind's worldview. He attended local schools before enrolling at Khalsa College in Amritsar, an institution founded to promote Sikh values and modern education. There, he pursued studies in theology and literature, fostering a deep appreciation for philosophy and religion. Khalsa College was not just an academic hub; it was a breeding ground for nationalist sentiments. During his time there, Thind became aware of the Indian independence movement, particularly the Ghadar Party, which sought to overthrow British rule through revolutionary means. Although he did not actively participate in armed resistance at this stage, his exposure to these ideas instilled a lifelong commitment to freedom and self-determination.

Before leaving India, Thind briefly worked in the Philippines as an oral translator, a role that exposed him to international travel and diverse cultures. This experience was a stepping stone, broadening his horizons and preparing him for the challenges of migration. By 1913, at the age of 21, Thind decided to seek opportunities abroad, joining a wave of Punjabi immigrants fleeing economic hardship and political persecution under British rule. Approximately 7,000 Punjabi men made similar journeys to the United States around this time, many of whom were Sikhs like Thind, drawn by promises of work and education. His departure marked the beginning of a transformative chapter, one fraught with discrimination but also rich with personal growth.

Immigration to the United States and Early Years

Thind arrived in Seattle, Washington, on July 4, 1913, aboard the steamship Minnesota from Manila, accompanied by his brother Jagat Singh Thind, who tragically died en route. This arrival coincided with a period of increasing anti-Asian sentiment in the U.S., fueled by laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and growing nativism. Despite these barriers, Thind settled in the Pacific Northwest, initially working in lumber mills in Oregon and Washington. These jobs were grueling, involving long hours in harsh conditions, but they provided a means to support himself and pursue higher education.

In Oregon, Thind became part of a vibrant South Asian community, many of whom were fellow Punjabis employed in agriculture and industry. He enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1914, where he studied theology and English literature, eventually earning a PhD. To fund his studies, he continued mill work during summers, demonstrating remarkable perseverance. It was during this time that Thind formally joined the Ghadar Movement, a revolutionary group founded in 1913 in Astoria, Oregon, by Indian expatriates aiming to liberate India from British control. Although he did not engage in direct actions against the British, his membership reflected his anti-colonial stance and connected him to a network of activists.

Life as an immigrant was challenging. Thind faced racial prejudice, including restrictions on land ownership and marriage for Asians. Yet, he remained optimistic, viewing America as a land of opportunity. His early years laid the foundation for his advocacy, as he began to articulate arguments for equality based on his Sikh heritage and Aryan ancestry, which he believed aligned with Western racial theories of the era.

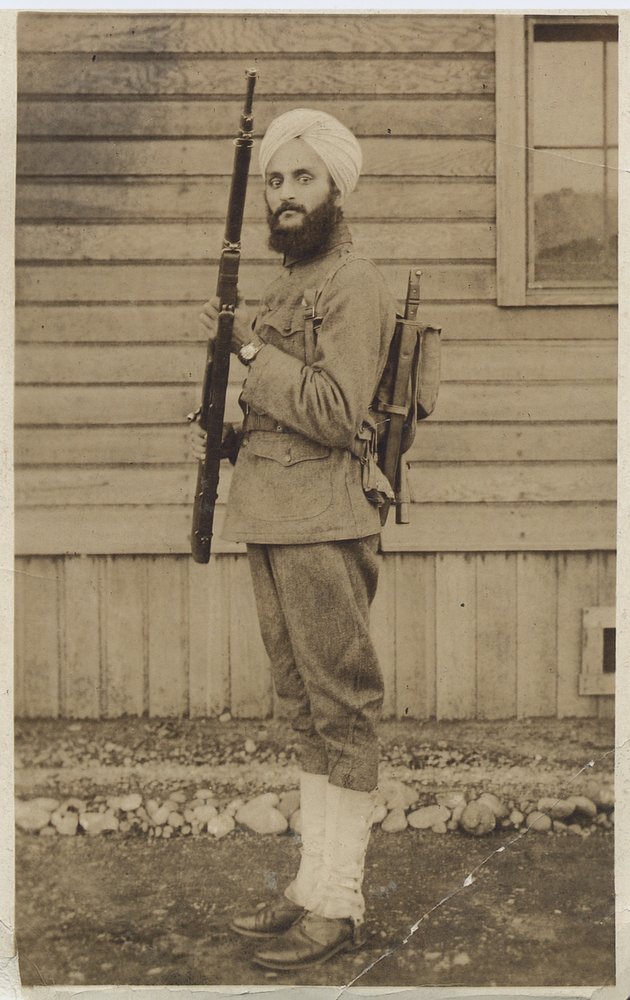

Military Service During World War I

As World War I raged, Thind's patriotism led him to enlist in the U.S. Army on July 22, 1918, at Camp Lewis, Washington. He was one of the first Sikh soldiers in the American military and notably the first allowed to wear a turban as part of his uniform for religious reasons, setting a precedent for future accommodations. Thind served in the infantry, rising to the rank of Acting Sergeant on November 8, 1918, just days before the armistice. His service was honorable, and he was discharged on December 16, 1918, with an "excellent" character rating.

Thind's military tenure was brief but significant. It occurred during a time when the U.S. was drafting soldiers from diverse backgrounds, yet Asians were often excluded from citizenship. His enlistment was a strategic move, as veterans were sometimes granted naturalization privileges. Thind's uniform symbolized his dual identity: a proud Sikh adhering to his faith while serving a nation that questioned his belonging. This experience deepened his resolve to fight for rights, blending his warrior heritage from Sikhism with American ideals of liberty.

The Citizenship Battle and Supreme Court Case

Thind's quest for U.S. citizenship began immediately after his discharge. On December 9, 1918, still in uniform, he applied in Washington state, but it was revoked four days later on racial grounds—he was deemed not a "white man" under the Naturalization Act of 1790, which limited citizenship to "free white persons." Undeterred, Thind reapplied in Oregon on May 6, 1919, and was granted citizenship on November 18, 1920, after the judge considered his military service and self-identification as a high-caste Aryan.

However, the Bureau of Naturalization appealed, citing Thind's Ghadar ties. The case escalated to the Supreme Court, culminating in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind on February 19, 1923. Justice George Sutherland ruled that while Thind might be Caucasian anthropologically, he was not "white" in the common understanding, revoking his citizenship. This decision affected over 70 Indian Americans, leading to denaturalizations and broader implications for Asian immigrants. Thind's arguments, rooted in racial science and Vedic texts, challenged prevailing notions but ultimately failed due to popular racism.

The ruling was a setback, but Thind persisted. In 1935, he applied again in New York under the Nye-Lea Act, which extended citizenship to World War I veterans regardless of race. He was finally naturalized in 1936, nearly two decades after his first attempt. This victory was personal and symbolic, paving the way for future reforms like the Luce-Celler Act of 1946, which allowed Indian immigration and naturalization.

Academic Pursuits and Professional Career

Following the Supreme Court loss, Thind focused on academia. He completed his PhD in theology and English literature at UC Berkeley, where he had begun studies earlier. His dissertation likely explored intersections of Eastern and Western philosophies, reflecting his lifelong interest in spirituality.

Professionally, Thind transitioned into lecturing and writing. He toured the U.S., delivering talks on metaphysics, Sikhism, and self-realization to diverse audiences, including universities and spiritual groups. His lectures drew from Sikh scriptures like the Guru Granth Sahib, while incorporating influences from Christianity, Hinduism, and American thinkers such as Emerson and Whitman. Thind's approach was inclusive, promoting meditation and inner peace as paths to enlightenment.

He also continued advocating for Indian independence, speaking at events and supporting the Ghadar legacy. His career as an educator and activist bridged cultural divides, earning him respect despite earlier rejections.

Spiritual Teachings and Writings

Bhagat Singh Thind's spiritual contributions were profound and far-reaching, establishing him as a bridge between Eastern mysticism and Western philosophical thought. He viewed Sikhism not merely as a religion but as a universal science of the soul, emphasizing that true spiritual realization comes through disciplined meditation, inner discipline, and direct union with the divine. Rooted in the Sant Mat tradition—a 12th-century spiritual path originating in India that stresses inwardness, inclusiveness, and the pursuit of the divine sound current or "Holy NAM"—Thind's teachings promoted a practical approach to spirituality, accessible to all regardless of background. He argued that religion must be universal and scientific, grounded in eternal wisdom rather than dogma, and he often critiqued modern society's separation from God, attributing it to ego-driven illusions and material distractions. Thind blended Sikh scriptures, such as the Guru Granth Sahib, with influences from Christianity, Hinduism, psychology, and American transcendentalists like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, and Henry David Thoreau, whom he studied during his time at Khalsa College and UC Berkeley. This synthesis allowed him to appeal to diverse audiences, presenting spirituality as a tool for overcoming worldly troubles through self-elevation and service to humanity.

Over his lifetime, Thind authored an extensive body of work, with estimates ranging from 18 to 40 books and pamphlets dedicated to spiritual science and self-realization. His early publications, such as Radiant Road to Reality: Tested Science of Religion (1923) and Science of Union with God (1924), laid the foundation for his philosophy, offering practical guidance on meditation techniques, yoga, breathing exercises, and the harmonization of mind, body, and spirit. These works emphasized that obstacles in life are opportunities for growth, famously stating that "service is the resistless energy to bring forth order out of chaos." In the multi-volume series Jesus, The Christ: In the Light of Spiritual Science (published in the 1940s), Thind reinterpreted Christian teachings through a Sikh lens, exploring themes of divine love, redemption, and the inner path to enlightenment across four volumes. Other notable titles include Divine Wisdom: Volume 1 – Man Is Deity in Expression (a collection of essays on physical manifestation and inner power), House of Happiness (a self-help guide to contentment through spiritual alignment), Winners and Whiners in This Whirling World (focusing on self-realization and individualism, with quotes from Whitman like "Not even God is so great as myself is great to me"), and Advanced Lessons (a deeper exploration of metaphysical concepts). These writings were often based on his lectures from the 1920s onward, making complex ideas accessible and popular, especially among young people.

Posthumously, his son David published additional titles, such as Troubled Mind in a Torturing World and Their Conquest (1939, republished later), which comprises 17 essays addressing modern spiritual alienation, with chapters like "Union with God," "The Unknown Is the Known," "Ego vs. Individuality," "Unification and Reunion," "Sikh Religion Made Plain," and "The Song of the Soul Victories." Disciples regarded this as his greatest work, highlighting how ego and societal chaos separate humanity from divine harmony. Other posthumous releases include Elite Minds, Elect Minds and Who are the Elect Ones? / Soul at Death: Volume 9, delving into advanced concepts of consciousness and the afterlife. Thind's teachings anticipated elements of the early New Age movement, influencing spiritual seekers with his emphasis on prosperity as a divine path, individualism, and universal love—ideas that echoed in later American spiritual trends like prosperity theology. He founded no formal organization or temple but inspired followers through personal mentorship and initiations, promoting equality, love across religions, and the idea that "dependence is slavery" while self-reliance leads to spiritual freedom. His legacy continues to resonate in Sikh-American communities and broader spiritual circles, with his family republishing his works to ensure their perpetual availability.

Personal Life

Bhagat Singh Thind's personal life was a tapestry of cultural transitions, familial duties, and romantic unions, reflecting his journey from rural Punjab to cosmopolitan America amid racial and legal challenges. Born into a prominent Kamboj Sikh military family, Thind was the eldest of three sons to Sardar Boota Singh Thind, a retired subedar major in the British Indian Army, and Isher Kaur, who passed away when he was young. His father raised the boys alone, never remarrying, and instilled values of discipline and independence. Before emigrating, Thind married Chint Kaur in India around 1912, but he left her behind when he departed for the Philippines and then the U.S. in 1913, possibly due to immigration restrictions or economic pressures. Details about this first marriage are sparse, and Thind later declared himself a widower on official documents, even though Kaur was alive, perhaps to navigate U.S. laws against polygamy or to assimilate more fully. This union did not produce children, and Thind focused on supporting his brothers financially from afar.

In 1923, shortly after his Supreme Court setback, Thind wed Inez Marie Pier Buelen, a white American woman and New Thought practitioner from Spokane, Washington. Born in 1891, Buelen shared Thind's interest in metaphysics and spirituality, and their marriage symbolized his integration into American society despite anti-miscegenation sentiments. However, the union faced strains, possibly from Thind's extensive travels and legal battles, leading to a divorce in 1927. Thind's third and final marriage was to Vivian Davies in March 1940, in the Collingwood Presbyterian Church in Toledo, Ohio. This partnership endured until his death, providing emotional stability amid his nomadic lecturing career. They maintained close contact through daily letters during his absences, and Vivian described him as a noble husband and devoted father. Together, they had two children: a daughter, Rosalind Stubenberg, and a son, David Bhagat Thind, who later played a key role in preserving and publishing his father's writings.

Despite public scrutiny over his interracial marriages and Sikh identity, Thind steadfastly maintained his religious practices, including wearing a turban and beard as symbols of faith and heritage. His family life offered a counterbalance to his professional demands, with Vivian's parents living with them, fostering a multigenerational household. Thind extended support to his extended family in India, including nephews like Charan Singh Thind, Harbhajan S. Thind, and Balwant S. Thind, whom he helped educate. He incorporated family values into his teachings, advocating for women's education, harmony in relationships, and living in the present—principles drawn from his father's advice before leaving India: avoid begging, adultery, intoxicants, and dwelling on the past. Thind's personal experiences of displacement and resilience infused his spiritual messages with authenticity, emphasizing happiness through inner peace and familial bonds.

Later Years and Death

In his later years, Thind settled in California, specifically the Hollywood Hills in Los Angeles by the 1940s, where he established a base for his spiritual ministry while continuing to lecture extensively across the United States, particularly in the Midwest. He ministered to thousands, initiating disciples into Sant Mat practices and delivering talks on metaphysics, self-realization, and anti-colonialism. Thind remained connected to the Ghadar Party, advocating for Indian independence, which kept him under British surveillance for nearly two decades. He witnessed India's independence in 1947—a cause he had championed through his writings and activism—and celebrated it as a triumph of self-determination. As civil rights movements gained momentum in the U.S. during the 1950s and 1960s, Thind's landmark citizenship case was reevaluated in historical contexts, highlighting its role in exposing racial injustices in immigration law. In 1963, he and Vivian traveled to India, receiving a hero's welcome; he met President Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, underscoring his enduring influence in both nations.

Thind continued writing prolifically, working on unfinished manuscripts that expanded his spiritual philosophies, and he shielded his son David from the details of his earlier struggles, instilling values of democracy, entrepreneurship, and faith instead. A month before his death, the Ghadar Party honored him, declaring no other Indian in the U.S. had contributed as much to India's freedom. Thind died suddenly on September 15, 1967, at age 74, in Los Angeles, while in excellent health and amid his ongoing work. His passing marked the end of an era for early South Asian American pioneers, but his ideas endured through his family, who republished his books and maintained a scholarship fund he established in 1916 for underprivileged students, now managed by David and relatives in India. Disciples like Jerry Tuttle and Dr. Amarjit Singh Marwah recalled his transformative wisdom, which dispelled notions of human sinfulness and promoted equality. In recent years, the 100th anniversary of his Supreme Court case in 2023 sparked renewed interest, with panels, documentaries, and publications examining his legacy in race, caste, colonialism, and spirituality. Thind's life continues to inspire, symbolizing resilience, spiritual innovation, and the fight for belonging.

Legacy

Bhagat Singh Thind's legacy is multifaceted. Legally, his Supreme Court case exposed the flaws in racialized immigration laws, contributing to reforms that enabled South Asian citizenship. Culturally, he pioneered Sikh representation in America, from military service to spiritual leadership. Modern media, including PBS documentaries and NPR podcasts, have revived his story, highlighting its relevance to ongoing debates on race and belonging.

Thind's life teaches resilience against injustice and the power of spiritual wisdom. As an immigrant who turned adversity into advocacy, he remains an inspiration for generations seeking equality and enlightenment in a diverse world.